KNOW

GREAT

HISTORIES

CONTEMPORARY

The wolf plays a key role in the biomes it inhabits. By limiting the behavior and overgrazing of its prey, these habitats increase their richness and diversity. Ecosystems tend to self-regulate once the wolf populations are of a sufficient size.

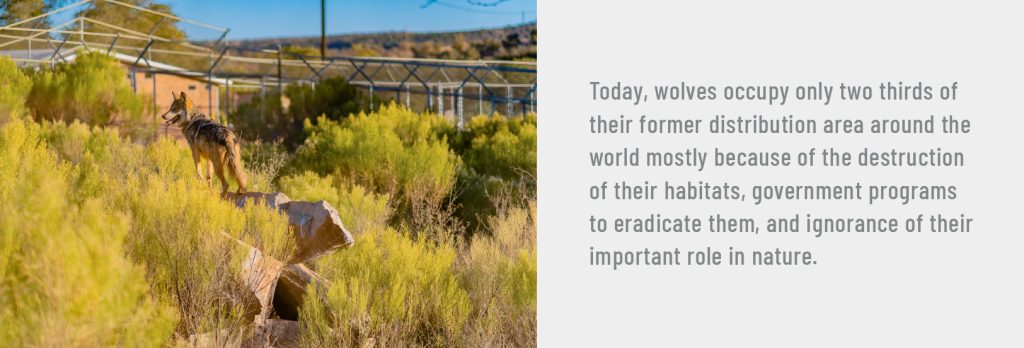

Wolves were once the most widely distributed land mammal in the northern hemisphere. They knew how to adapt to a wide variety of climates and ecosystems, from the temperate forests of the mountain regions to the grasslands of the prairies, from the tundra in Greenland to the Negev desert in southern Israel, withstanding temperatures ranging from -68°F to 122°F (-56°C to 50°C).

The diversity of their habitats and climates is reflected in the physical characteristics seen in wolves that live in different parts of the world. Various authors in the scientific community identify two primary species of wolves: the gray wolf (Canis lupus) and the red wolf (Canis rufus). Globally, the conservation status for the gray wolf (Canis lupus) is Least Concern, while the red wolf (Canis rufus) is Critically Endangered, according to the International Union for Conversation of Nature.

The Mexican gray wolf is the most distinctive subspecies of gray wolf, genetically speaking, and it plays an essential role in achieving ecological balance:

The real conflict with the wolf began in the 16th and 17th centuries with the introduction of livestock farming in Mexico and the United States. During the first half of the 20th century, the US government, through the Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS), led a campaign to eradicate the Mexican gray wolf as part of a strategy to grow the livestock industry. In the mid-1950s, Mexico entered into an agreement with the US Fish & Wildlife Service to “control” the wolf and coyote population under the pretext of eliminating wild rabies and because of “serious depletion of livestock”.

The Mexican wolf was hunted and poisoned to such a degree that by the 1970s, this subspecies had all but disappeared in the United States, and in Mexico it was on the brink of extinction. Between the extermination campaigns in the United States at the beginning of the last century, and then in Mexico, the wolf was nearly completely eradicated.

Major efforts to rescue the Mexican gray wolf began in the 1970s:

These three lineages form the basis for a binational captive breeding program to save the Mexican gray wolf from extinction. Thanks to the work of different zoos and similar facilities in both Mexico and the United States, the genetic challenges were overcome, and the numbers of Mexican gray wolves are now beginning to increase.

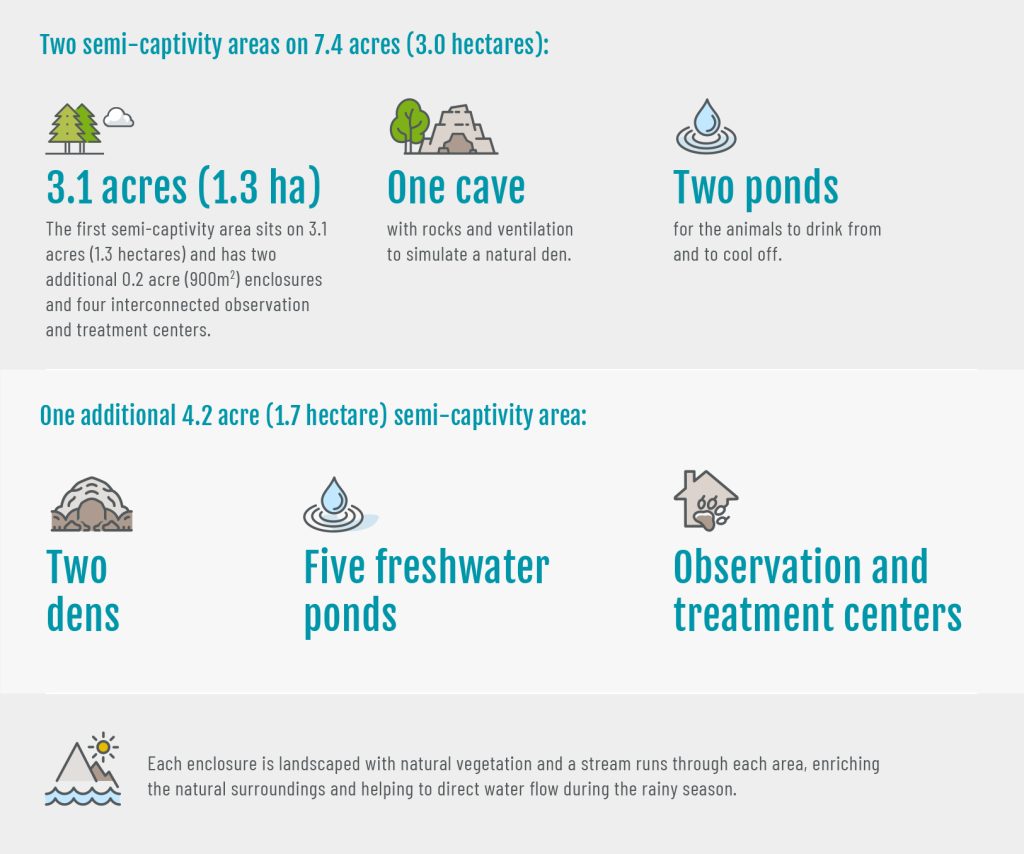

The Buenavista del Cobre Wildlife Conservation Center in Cananea is one of only two facilities in Mexico doing work to prepare individuals to be released into their original habitats.

This 445 acre (180 hectare) facility was opened in 2012 and includes dedicated spaces for mating, breeding, and the pre-release of different species. Este espacio es considerado por el Comité Binacional para la Conservación del Lobo Mexicano (México-E.U.A) como el más grande e importante en el país destinado para la conservación del lobo gris mexicano, el cual cuenta con:

Because of the genetic importance and value of the species, when litters are born at the Buenavista del Cobre Wildlife Conservation Center, they receive veterinary care that includes vaccination, parenteral and systematic deworming, weight monitoring, identification microchips and flea collars, zoometry and taking of samples for blood biometry and chemistry.

The first reintroduction of the species in Mexico occurred in October 2011 with a family of wolves in the Sierra San Luis, Sonora. This site was selected for its favorable conditions with hydraulic dams and a stable natural habitat.

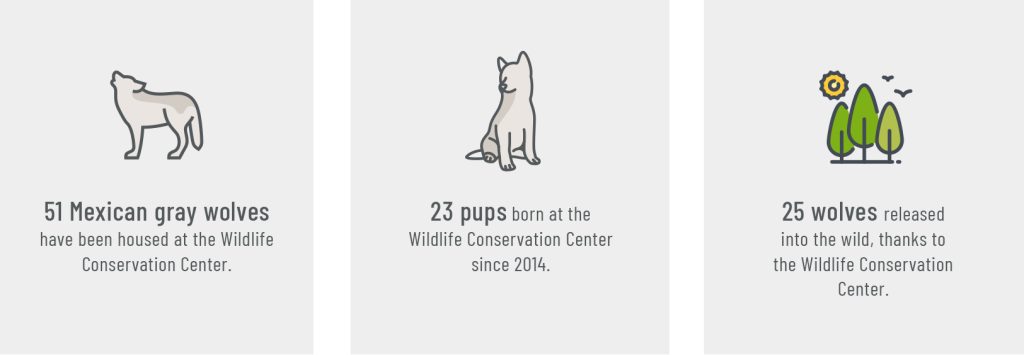

A total 67 Mexican wolves have been released into the wild between 2011 and 2021 through 17 releases. More than 40% (twenty-seven individuals) were transferred from the pre-release areas at the Buenavista del Cobre Wildlife Conservation Center to:

Unlike the national parks in other countries where the land is owned by the state, 92% of the Protected Natural Area lands in Mexico are owned by ejidos, communities or in private hands. This makes the conservation of the Mexican wolf more difficult as their survival will depend on the tolerance of the community landowners and their coexistence with the wolves in the long term.

An effective conservation strategy for the wolf and other key ecosystem predators, is privately-owned land and Areas Voluntarily Designated for Conversation (in Spanish, ADVC):

These results make the Buenavista del Cobre Wildlife Conservation Center the primary pre-release center in the country, thanks to our efforts in conjunction with the Mexican National Commission on Protected Natural Areas (in Spanish, CONANP), the Mexican Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (in Spanish, SEMARNAT), and a team of veterinarians and Mexican gray wolf specialists.

Today, there are nearly 45 wolves in the wild in Mexico in and around the Janos Biosphere Reserve in Chihuahua, while in the United States, there are 186 wolves living, primarily, in two national forests: Gila and Apache Sitgreaves. The challenges to increase these populations and to keep them stable in the wild are enormous

The wolf is essential to the ecosystems that are characteristic of a biogeographical zone. The destruction of their habitat and ignorance of their important role in nature threatened their survival and the proper balance of the biodiversity and other ecological conditions in the region.

Thanks to the combined efforts of governments, private initiatives, veterinarians and specialists, the Mexican gray wolf has been downgraded from “probably extinct in the wild” to “endangered species”.

Although there are still many challenges in the conservation of this species, the actions of our Buenavista del Cobre Wildlife Conservation Center affirm the commitment of Grupo México to the conservation of biodiversity and the environment in the places where we operate.